States which had the necessary ecosystem and an enabling environment for the manufacturing sector to grow could reap the positive impact of changes in labour laws sooner than others.

A study undertaken by a think tank under the Union Labour Ministry reveals that in states which reformed labour laws, the average plant sizes went up and so did formal employment in the manufacturing sector. There are exceptions though, which are explained by the varying level of industrialisation and nature of industries in different states.

Key reforms that the study by VV Giri National Labour Institute looked at were: i) raising the worker threshold to 300 from 100 for exempting companies from seeking government nod to shut down, ii) increasing the threshold under the Factories Act from 10 to 20 for units drawing power and 20 to 40 for those not drawing power, for purposes of regulatory compliance, and iii) introducing fixed term employment in textiles and apparel sector.

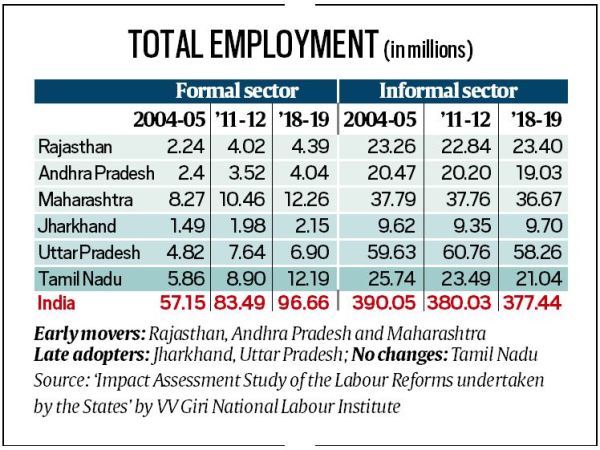

The study put sample states under three buckets: i) early movers in 2014-15 — Rajasthan, Andhra Pradesh and Maharashtra, ii) those which checked in later between 2017 and 2020 viz., Uttar Pradesh and Jharkhand, and iii) finally states like Tamil Nadu which did not undertake any reforms.

The impact seems to be heterogeneous across states and over time. For instance, while Rajasthan made amendments raising the worker threshold in 2014, no significant impact was visible till 2017 in comparison with Jharkhand which amended its labour laws in 2017. In contrast, a positive impact was visible in Maharashtra within a year of changes with a rise in total mandays and plant size, when seen in comparison with Tamil Nadu, which did not amend its labour laws.

The study attributes this heterogeneity to the industrialisation level in the states. Those which had the necessary ecosystem and an enabling environment for the manufacturing sector to grow could reap the positive impact of changes sooner than others. “This indicates that labour reform is just one element in the overall policy mix and if it has to act as a catalyst and show effects quickly, then other prerequisites need to be in place a priori,” the report says. It, however, underscores the point that absence of any significant results cannot be interpreted as a negative impact of the amendments.

As far as employment is concerned, all states witnessed a steady increase in absolute terms between 2004-05 and 2018-19. Four states — Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Andhra Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh — saw a larger increase in employment in the first block of seven years (2004-05 to 2011-12). Other states such as Tamil Nadu, Rajasthan, Maharashtra and Jharkhand saw a larger increase in the second block of seven years (2011-12 to 2018-19). Andhra Pradesh (an early mover) and Uttar Pradesh (which amended labour laws much later in 2020), however, recorded a marginal decline in employment in the second block of seven years between 2011-12 and 2018-19. As can be seen, these trends do not establish any causal relationship between employment and labour laws.

While the overall manufacturing sector had a “relatively sluggish performance in terms of employment generation”, the organised sector within manufacturing did better with employment rising by 1.7 million in the post-reform (2014-15 to 2017-18) period compared with 1 million in the pre-reform (2010-11 to 2014-15) period.

For units with 300 or more workers, an early lead on labour reforms by states such as Rajasthan and Andhra Pradesh saw employment in their manufacturing firms increase by 10.3 percentage points from 40.9 percent in 2010-11 to 51.2 percent in 2017-18, and 7.1 percentage points to 54.3 per cent from 47.2 per cent, respectively. Other states such as Uttar Pradesh, which has its own Industrial Disputes Act and is not governed by the Centre’s ID Act, recorded a 4.8 percentage point increase, while Maharashtra recorded a 4.7 percentage point increase during the same period. Tamil Nadu, which has not undertaken any labour law amendments, saw its employment in manufacturing firms increase by 8 percentage points to 55.1 per cent from 47.1 per cent during the period.

“This increase in the share of employment in large plants with 300 or more workers and a decline in share of plants with workers less than 299 during the periods under study also indicate that the firms are moving towards achieving economies of scale and scope which would have a positive bearing on the competitiveness of manufacturing products and in turn on the overall economy,” the report notes.

The increase in share of employment in large plants was also reflected in the increase in average plant size across states. For instance, over 50 per cent of employment in the manufacturing sector in all states was in units with 300 or more employees, with the share of employment in these units rising from 51.1 per cent to 55.3 per cent from 2010-11 to 2014-15, and to 56.3 per cent by 2017-18. Jharkhand, one of the states with abundant natural minerals, was an outlier with about 68 per cent of total manufacturing employment reported in plants with 300 or more employees in 2010-11, which then slipped to 63.8 per cent by 2017-18.

Source:indianexpress.com