Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has upended global energy markets and, if stability doesn’t return soon, that could have serious geopolitical consequences for OPEC members. The pre-invasion hydrocarbon markets were almost in equilibrium, as stable global economic growth combined with rational management strategies from the OPEC+ alliance to balance markets. Despite a global pandemic that disrupted the global economy for two years, energy markets had managed to return to a level of relative stability. Some were even predicting a post-Covid order in which OPEC+ would experience an era of strong influence and power. Today, the OPEC+ alliance appears to be hanging by a thread as Russia faces an economic crisis on the back of sanctions imposed in response to its invasion. The ongoing shift inside OECD countries, especially the EU, the UK, and the U.S., to wean themselves off Russian energy supplies, is dramatic and could prove to be influential in isolating Russia from the wider energy market.

At a time when global oil and gas markets were already facing some supply issues, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine really threw fuel on the fire. Western energy-dependent countries are now calling on others to increase oil and gas production and exports not only to quell the global thirst for energy but also to counter the rapid rise in prices. All eyes are on OPEC, as the oil exporters group, some call it an oil cartel, is considered the only viable option in the short term to supply more. Until now, all calls from Washington, London, and Brussels appear to have fallen on deaf ears. In a seemingly desperate move to influence OPEC’s leaders, British PM Boris Johnson flew to Saudi Arabia, officially to discuss possible investment agreements, but mainly to push for additional oil volumes from the Kingdom. During meetings with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, the defacto ruler of the Kingdom, and his counterpart Abu Dhabi Crown Prince Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed, Johnson pushed for additional oil supplies, while also discussing Western sanctions on Russia. The Prime Ministers’ efforts, however, have been met with silence, no new energy promises have been made by either party.

According to Johnson, when asked about a potential change in OPEC’s production strategies, MBS and MBZ both made it clear that they understand the need for stability in the global oil and gas markets. The real answer from both OPEC leaders was very clear indeed, at this moment they will not change their production and export strategies and they will not endanger their strong relationships with Russia’s leader Putin. These responses were not particularly surprising for analysts.

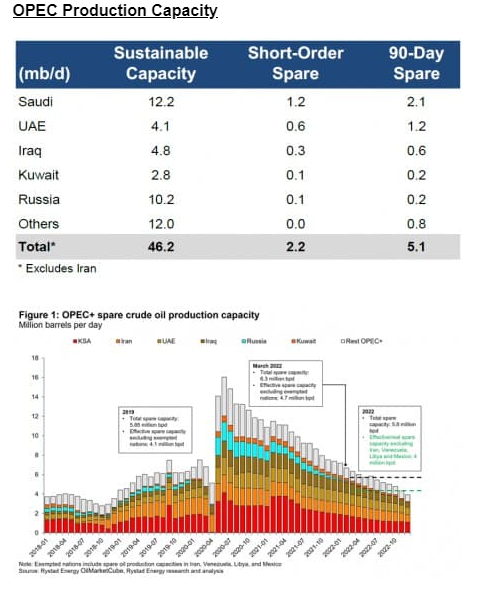

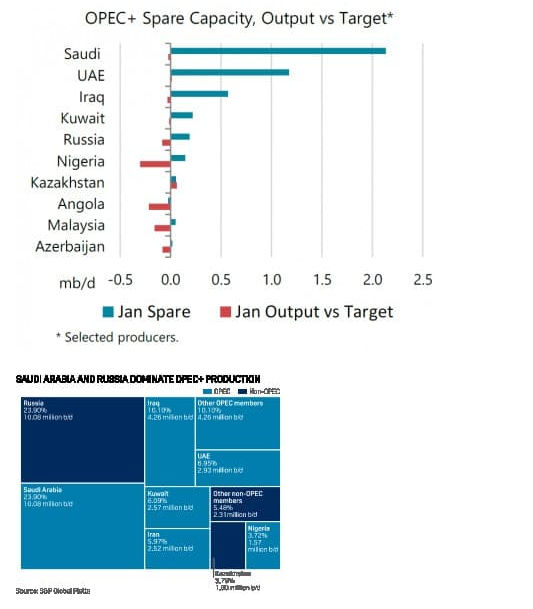

OPEC has always prided itself on maintaining a healthy spare production capacity in order to influence oil markets. For decades, OPEC producers have been the center of attention for traders, importers, and financial analysts, and have always been considered the ultimate resource for energy in case of a global crisis. Saudi Arabia, and lately also Abu Dhabi, have been seen as the ultimate swing-producers that clients could rely on if a sudden geopolitical or technical issue were to occur blocking potential suppliers. The Kingdom is still seen as the ultimate swing-producer, holding a spare capacity of between 1.2-2.1 million bpd. In the last couple of years, Abu Dhabi’s upstream expansion has pushed it into a position of being a swing producer, with 0.6-1.2 million bpd. Riyadh’s geopolitical power position is directly related to this theoretical production capacity, as it mitigates the removal of Iran or Venezuela from oil markets. Abu Dhabi’s extra volumes are becoming increasingly important in such a tight oil market. Before the pandemic, US shale companies were also seen as swing producers, even if their long-term production capacity differed.

Since the end of the pandemic (which was the first time that global analysts seemed to understand that the market was heading towards a supply crisis), the market has had to reassess this narrative of spare capacity. The lack of new oil and gas investment and discoveries in recent decades has left oil markets drastically unprepared for such a shortage. Some have warned that part of the current OPEC+ export strategy is based on internal capacity constraints. In a market that was slowly recovering from major demand destruction, OPEC members could hide their domestic production constraints behind the facade of a conservative production policy. Now, with Russia in crisis and an oil shortage looming, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and other members will need to put their money were their mouth is. If they fail to act now, rumors about a lack of spare production capacity will become increasingly believable. Current analysis already indicates that most OPEC producers are incapable of increasing production. Saudi Arabia and the UAE are believed to have higher capacity, but the current silence from both players is not going to instill confidence in observers.

A possible reality is hovering on the horizon in which 4+ million Russian oil barrels are stuck on Russian soil and the market is unable to find a substitute for them. If Saudi Arabia and the UAE are not able to supply that much-needed 2-3 million bpd to Western markets, oil prices will soar to unseen heights. A potential failure to find a swing-producer would not only lead to a real energy price crisis but would also undermine the current strategic power OPEC holds. Geopolitically, OPEC producers’ attractiveness to others (financial markets, manufacturers, and investors, but also defense/security) is linked to their oil and gas supply capabilities. Without this, the entire geopolitical equation will change.

Saudi Arabia, Iraq, the UAE, and Kuwait have 4 million bpd of spare capacity – in 3-6 months

By Cyril Widershoven for Oilprice.com

Source:oilprice.com