A skeleton of the biggest animal to have flown during the Middle Jurassic was found on the Isle of Skye, Scotland. This is one of the best-preserved fossils in UK’s history, researchers who discovered it told DW.

Written by Esteban Pardo

Scotland is well known for its cloudy days and constant rain. One hundred and seventy million years ago, it was much warmer and tropical ― and it had huge reptiles with a wingspan of 2.5 meters (8.2 feet) soaring the skies.

That’s what researchers learned from a fossil that was discovered on the Isle of Skye, in northwest Scotland. The findings were published in Current Biology earlier this week and describe the biggest pterosaur from the Middle Jurassic period discovered so far.

The new species is called Dearc sgiathanach pronounced “jark ski-an-ack,” which is a Scottish Gaelic name meaning both “winged reptile! and “reptile from Skye.”

The discovery is “a superlative Scottish fossil,” Stephen Brusatte told DW. The paleontologist at the University of Edinburgh led the National Geographic Society-funded expedition that found “Jark” back in 2017.

He was referring to the state of preservation of the fossil, “far beyond any pterosaur ever found in Scotland and probably the best British skeleton found since the days of Mary Anning in the early 1800s,” he said.

Anning was a famous English paleontologist from the first half of the 19th century who discovered many fossils, including the first pterosaur skeleton outside of Germany.

Flying reptiles, not dinosaurs

Pterosaurs, or pterodactyls as they are commonly known, were flying reptiles that existed from the Late Triassic, which was around 228 million years ago, to the end of the Cretaceous, 66 million years ago, when an asteroid wiped out almost all life on Earth.

Pterosaurs were the first vertebrates to fly. For those who grew up with the movie series “The Land Before Time,” they may be already familiar, since Petrie, one of the main characters, was a Pterosaur.

Even though their name might suggest it, pterosaurs are not dinosaurs. They are close cousins that evolved on a different branch of the reptile family tree.

Before the discovery of this fossil, scientists used to think that pterosaurs were rarely bigger than 1.6 meters during the Triassic and the Jurassic, Brusatte said, but “now we know they were capable of getting much bigger.”

A very rare fossil

The fossil was spotted in 2017 by then-PhD student Amelia Penny at the shores of the Isle of Skye, at a place known as Brothers’ Point. She saw part of the jaw and teeth protruding from a lime stone.

Brusatte said team members became excited when they found out that it wasn’t just a skull but a whole skeleton. He said it was a challenge to free the fossil from the rock, because the tide was rising quickly, so they had to wait until midnight, when the water had receeded, to finish cutting the fossil out of the rock.

The team had to leave the find overnight until members were ready to carry out the full excavation the next morning, Brusatte said, praying that no one would stumble into the precious fossil.

Natalia Jagielska, lead author of the paper, told DW that another thing that makes this fossil so rare is that it’s already hard to find any Middle Jurassic fossils, but it’s even harder to find pterosaurs.

“They are very rarely preserved in the fossil record,” Jagielska said. “They are very very delicate, have very thin bones and get crushed.”

Picturing ‘Jark’

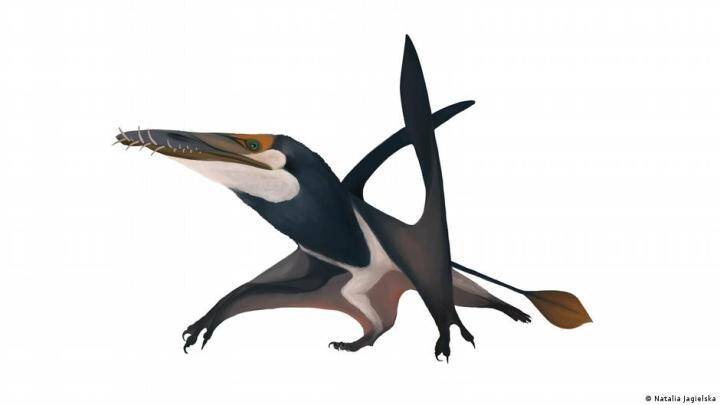

So what might D. sgiathanach have looked like?

Although the degree of preservation was remarkable, the fossil still had many missing parts.

That’s why, Jagielska said, it took detective and forensic work to get an idea of its appearance. The team used a lot of other pterosaur fossils from many different museums to fill in the blanks and complete the puzzle.

Jagielska, who is also an illustrator, described the pterosaur as a creature with four legs and a 2.5-meter wingspan — close to that of an albatross. Its forearms were modified into wings and much larger than its hindlegs, and it had four fingers, with the fourth one being very elongated to extend its membranous wings, similar to modern bats. It also had a long tail for balance and very sharp teeth, most likely for fish catching.

A deeper look into its skull revealed that it probably had good eyesight and a very good sense of balance, “both features very helpful for a flying animal,” Jagielska said.

And: The skeleton didn’t belong to an adult. When analyzing bone slices under the microscope, the Scottish researchers found out that D. sgiathanach was still growing.

Jagielska said she wanted people who see the fossil on display at the National Museum of Scotland them to take a moment and think about the fact that they ar0e looking at the remains of an animal that was flying over Scotland 170 million years ago, “preserved with many of the features it had when living.”

Source: indianexpress.com