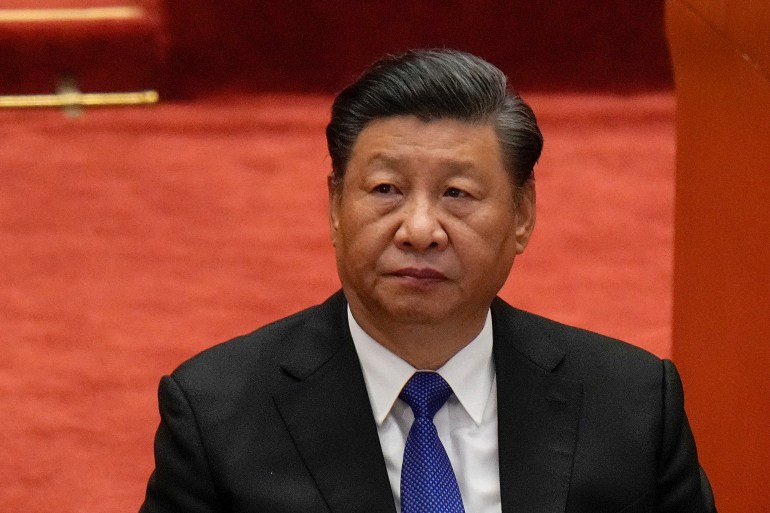

China is facing a demographic time bomb that threatens to upend Xi Jinping’s economic plans.

By Simina Mistreanu

China needs more children to defuse a demographic time bomb that threatens to derail President Xi Jinping’s ambitions to double the Chinese economy by 2035.

To achieve that goal, Beijing is corralling local administrations and businesses to encourage reluctant women to give birth – by offering everything from baby bonuses, to discounted mortgages and paid leave that increases depending on the number of children.

Since May, when China started allowing families to have up to three children after decades of draconian family-planning policies, local officials and firms have pushed a slew of incentives at prospective parents.

Dabeinong Group, an agricultural technology company in Beijing, has been heralded as China’s most generous employer for expecting parents due to benefits that include up to 90,000 yuan (US$14,100) in cash and additional leave of up to 12 months for new mothers and nine days for fathers. Chinese law provides for 98 days of maternal leave but no time off for fathers.

Dabeinong Vice President Chen Zhongheng said earlier this month the firm had adopted these measures “because the government is encouraging births”.

Cash gifts start at 30,000 yuan ($4,740) for couples having their first baby, with the amount doubling and tripling for the second and third child, respectively. The company also plans to increase maternity leave by one month, three months and 12 months, respectively, on top of what the government guarantees.

“We believe that department heads should take the lead in having more babies,” Cheng said, according to the South China Morning Post. “They should play a leading role as long as their age and condition allow.”

In December, the northern province of Jilin announced it was offering loans of up to 200,000 yuan ($31,500) to married couples planning on having children, plus tax breaks and cash. Meanwhile, the eastern city of Nantong is offering housing subsidies of 400 yuan ($63) per square meter to families with three children, while in Zhejiang province, couples with more than one child can access a higher ceiling for low-cost housing loans.

In one of the most dramatic moves so far, Beijing last year banned private tutoring to ease parents’ financial and social pressures, which are often cited as a major reason for not wanting children.

The push for more babies marks a reversal of China’s notorious one-child policy, which stood in place for four decades until 2015.

While the policy was intended to prevent overpopulation, its unforeseen consequences now threaten the foundations of the world’s second-largest economy, as a growing imbalance between working age and elderly people looks set to dampen economic growth, overload welfare services and disrupt social stability.

The problem for Beijing is that many women refuse to have more – or any – children. After the end of the one-child policy, the country only initially saw an uptick in the number of births, followed by five consecutive years of decline.

Last year, China’s birthrate dropped to a record low of 7.52 per 1,000 people, with just 10.6 million births — a number lower than in 1961, when Mao Zedong’s Great Leap Forward caused widespread famine and death.

“China’s population problem is beyond everyone’s imagination,” Yi Fuxian, a senior scientist in obstetrics and gynaecology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, told Al Jazeera.

Turning point

China’s population is expected to start shrinking in 2022, though many experts say the seismic turning point has already occurred.

The government’s all-out effort to reverse the trend is spurred by the fact that the country’s big-picture economic plans hinge on the demographic balance being maintained.

President Xi Jinping’s assertion in November 2020 that it was “completely possible” to double China’s gross domestic product by 2035 was based on overly optimistic projections that the population would not start shrinking until 2031, Yi said.

“The premature negative growth of China’s population means… the decline in economic vitality will also exceed expectations,” he said.

“The future will be turbulent. Everyone should fasten their seat belts.”

For many of China’s affluent and highly educated women, the efforts to make child rearing more appealing are too little, too late.

“Having a child would result in no time, no money and no freedom,” Kavita Yang, a 40-year-old university professor in Beijing, told Al Jazeera, asking that she be referred to by a pseudonym.

Yang decided last year she was not going to have a child after being on the fence about it for years. A child would require an investment of time, energy and money that she realized she was not willing to make.

Her decision was influenced by social expectations that women do housework and care for children – even when also putting in long hours at the workplace. The oversized responsibilities don’t come with matching privileges: women in China cannot carry on family lineages, while many complain they are denied the kind of support from their own families that would be a given for men.

Younger women especially are even eschewing marriage: A survey released by the Communist Youth League in October showed among 2,905 unwed urban residents aged 18 to 26, almost 44 percent of the women said they either had no intention of getting married or were unsure whether it would happen — almost 20 percentage points higher than for men in the same category.

Younger women especially are even eschewing marriage: A survey released by the Communist Youth League in October showed among 2,905 unwed urban residents aged 18 to 26, almost 44 percent of the women said they either had no intention of getting married or were unsure whether it would happen — almost 20 percentage points higher than for men in the same category.

Han believes that perks such as baby bonuses and extended parental leave fall flat for women after a lifetime of being seen as inferior to men, discriminated against in the workplace and saddled with responsibilities.

“At the core of the issue, it is about gender inequality within the family and the rising costs of children’s education and development,” Mu Zheng, an assistant professor of sociology at the National University of Singapore, told Al Jazeera.

Although women make up more than 50 percent of China’s college graduates, advances in education and the workplace are not yet reflected in family dynamics and the public discourse, Mu said.

“Men should be encouraged to take leave and get involved in parenthood,” she said. “Otherwise, with entrenched gender norms, women, particularly those with better education and career prospects, will become increasingly reluctant to have children.”

Some companies are trying out more holistic forms of support for women. Trip.com Group, China’s largest online travel company, offers flexible work schedules and free taxi rides for pregnant employees, subsidises education costs and even pays female employees to freeze their eggs, Jane Sun, the company’s CEO, told Al Jazeera.

As a result, Sun said, women make up more than half of the company’s workforce, more than 40 percent of middle management, and more than a third of executives.

Yang, the Beijing university professor, said Chinese society is overdue for a reckoning about the mental and physical burdens of childrearing placed on women — burdens that are tied to men often not rising to the occasion.

Until then, she cannot imagine having children.

“Taking good care of myself first is my main responsibility to my country,” she said.

SOURCE: AL JAZEERA