Amazon fishers are cashing in on a booming maw industry fuelled by Chinese demand, but the threat of overfishing looms.

By Lulu Ning Hui and Sarita Reed

Belem, Brazil – It was 7am on a day in late October last year and Belem, a port city in northern Brazil lying on the edge of the Amazon rainforest and about 100km inland from the Atlantic Ocean, was already sweltering hot.

Belem’s Ver-o-Peso open-air market, one of the largest in Latin America, was starting to get crowded with customers who came to buy from the colourful tropical fruits, herbs and vegetables on offer. Nearby, on the river, was the fish market, housed in a 19th-century iron building with high ceilings. Fishmongers had set up fish caught in the Amazon River and the Atlantic, which arrived at dawn. The salty odour of fish – new and old – hung in the humid air. Rows of stalls displayed their wares while sellers skilfully gutted fish as they waited for customers, setting the bones and heads to one side.

While fish is not cheap in Para state, where Belem is the capital, for most people these days it is more affordable than red meat or chicken. The meat stands opposite the fish market are almost all closed, and those that remain get few customers.

Claudio, in his 50s, has been selling seafood for 30 years. He guts and cleans several fish to put on display. He leaves in the maw – the swim bladder, an air-filled organ that controls the fish’s buoyancy in the water. He neatly lays out the fish, their bladders visible. There is still blood surrounding the bladders and their shape is full. Locals won’t eat internal organs, but, he says, “customers see the fresh-looking maw and know the fish is also fresh.”

The acoupa weakfish, however, known locally as the “pescada-amarela” in Portuguese or “yellow croaker” and one of the more expensive fish on sale, has arrived already gutted. Their maw never reaches the market. “It’s been sold long ago,” Claudio says.

Yellow croaker meat sells for 20 reais ($3.55) per kg, he explains. But to his knowledge its maw costs 2,800 reais ($497) per kilogramme.

“Expensive, so expensive,” he says. The minimum monthly wage in Brazil is 1,212 reais ($215). Fish maw from some species aren’t worth a cent, while others sell for exorbitant prices. He looks up from his weighing scale, “They all get sold to China.”

‘Gold in the sea’

A few days later, it is the afternoon in Ajuruteua, a fishing village of about 300 people, located several hundred kilometres north of Belem. A fisher rushes between his boat by the beach and a van where he transfers his catch – hundreds of thousands of small sardines.

He sells sardines for two reais ($0.35) per kg and says bigger boats use them as bait to catch yellow croakers, particularly for their maw. He knows about the sale of maw but has little clue why the Chinese buy them.

One woman in her 60s, whose husband and son were out fishing at sea, explains to us at the village cafe that her family can’t afford the bigger nets needed to catch yellow croaker. If they are ever lucky enough to net one, she says, it is like striking gold because of the high prices they command but also because of the croaker’s attractive shimmer.

“It’s like gold in the sea,” fishers we spoke to said of the yellow croaker.

Ajuruteua’s long, white beach, once packed with fishers using a traditional method to catch fish that involves setting up a trap using thin pieces of wood and snaring the catch when the tide goes out, is now almost empty, waiting for the city folks who come for the weekend. The method, called corrals, no longer works. Fewer fish now come close to shore and many residents have since turned to tourism. For those who still fish, but don’t have the money to invest in a bigger fishing boat or net, yellow croaker “gold” is out of reach.

The yellow croaker, found in abundance on Para’s coast, has only recently become valuable.

The reason is something of a mystery in villages where maw is produced. People we met in Para’s fishing communities shared different theories.

Claudio from the fish market in Belem believes it is used to make perfume, while a female fisher suggests, “maybe it’s for beauty products.” Based on the gelatinous texture of soup made from dried maws, some fishers believe they are used to make glue or plastic.

“When I was a child, I was sure the maw can be made into computer parts,” said a businessman who grew up in a fishing family, thinking of the hefty price tag.

Those familiar with the trade in various fishing villages know that prices differ between maw from male and female fish and that male bladders are more expensive, although they don’t know why. One former fisher thought he had the answer, “Is it an aphrodisiac?”

In China, dried fish maw is widely considered to have medicinal properties, which depend on the species, size, age, sex and origin of the fish. Male fish maw from yellow croakers fetches a higher price because customers believe they swim more in deeper waters and thus have stronger bladders, and therefore better collagen, which is desirable both for its medicinal value and its texture in a soup. Some consumers swear by maw’s medicinal benefits, others see it as a delicacy. As a result, fish maws are sought from around the world.

For fishers on Brazil’s Amazon coast, catching yellow croaker fish maw for export has increasingly become a vital source of income. Some are making a fortune from organs that were previously discarded.

Yet, a lack of fishing regulation could mean that, like any gold rush, this boom could end.

The growing maw market

Many of the fish sold in Belem comes from Vigia, a fishing port that lies 100km (62 miles) to the city’s north. This town of 55,000 residents has a natural harbour and, like Belem, lies on the Marajo Bay, nestled in a river inlet, and sheltered by a densely vegetated island. Boats heading out to sea through the bay soon reach the Atlantic Ocean where freshwater and saltwater meet. This means good fishing.

A historical text from 1830 about the Para region mentions fish maw exports. More than 30 tonnes of fish maw were exported annually between 1874 and 1878 to the US and Europe where it was used to make gelatin and isinglass, to filter wine and beer. Fish maw was sold to China as early as the start of the 20th century, but only in the last decade have quantities and prices rocketed.

Whatever its use, today’s fishers are eager to take advantage of fish maw’s growing market in Brazil and its high prices.

In the quiet village of Itapua near Vigia, the tide has gone out in the early afternoon and Elder Junior’s small wooden fishing boat sits silently on the silt. Junior, 37, smiles as he mends his nets, the shuttle in his hand moving rapidly back and forth sealing the edge of a large fishing net.

He returned from the sea a few days ago. He and three other fishers spent 10 days in a boat less than five metres long. They brought back 40 yellow croakers, a total of 142kg (313 pounds).

It was a good catch. The flesh alone will just cover the cost of fuel. The fish maw is all profit. In other words, going out would be pointless if he couldn’t sell the maw. “When my daughter was young, I used the fish maw to make dolls for her,” Junior says laughing. Of course, he doesn’t do that now.

Junior started fishing when he was 12 years old. The extra income from fish maw, especially when its price started to go up 10 years ago, has made him much more confident about the future. The first time his 10-year-old son set foot on a boat, he got seasick. But Junior is glad, “That means he’ll be happier going to school.”

His family have fished for generations, but he hopes his children will do something else.

Despite the returns, it’s a harder life for Junior than it was for his father, he says, since there are more boats to compete with, including the big ones.

At high tide the following day, a large boat arrives in Vigia after weeks at sea. It unloads hundreds of yellow croakers from the hold – all with the maws removed. From another boat, a bag of dried fish maw of all sizes is swung onto the dock where a car has been waiting. Two young men emerge from the driver’s seat, grab the bag, take a quick look and tuck it into the boot. They ignore our calls for a chat and drive off.

The supply chains between the Amazon and the end market on the other side of the world aren’t complex. The fish maw is often removed from the fish and cleaned and dried while the boat is still at sea. The boat owner then sells the fish maw to buyers — sometimes directly to the exporters, but more often to the first in a series of traders.

The exporter then ships the fish maw to Hong Kong by air or by sea. Brazil’s fish maw producers say Hong Kong is both a consumer and a re-exporter of fish maw. Much of it is smuggled into mainland China, where the various food safety-related permissions that are needed are an obstacle to direct exports.

Most of the profit in Brazil goes to the traders and exporters. A local researcher who would only speak on the condition of anonymity due to fears that being associated with investigations into the trade would affect their own work, said, due to the huge profits, people in the trade do not like to speak about it and very little is known of this growing market.

Traders carry plenty of cash and so keep a low profile. Robberies have targeted traders. In interviews, we were told that some export companies fit the vehicles transporting fish maw with bulletproof glass and that Chinese merchants have been targeted by local criminal gangs.

Insiders tend to be quiet. But for an industry that has kept a low profile, in recent years it is no longer conspicuous, with hundreds of people in the trade, according to Marcius Santos, a partner in a firm exporting fish maw who agreed to talk to us.

Boom brings fierce competition

Marcius Santos, a confident man with a square, boyish face, doesn’t look his 46 years. Eating fish maw keeps him young, he jokes.

This local trader hails from a fishing family and started trading fish in his 20s. In 2018, he teamed up with Huang Wei, a Chinese businessman from Jiangmen in Guangdong province, to export fish maw.

In Braganca, a town on the Atlantic coast of northern Para, Huang opens the company’s warehouse, a small room behind a locked door in their cleaning and drying facility. It smells like a fish market.

Fish maw of all shapes and sizes, cleaned and dried, sit in sacks waiting to be flown to Hong Kong. “These are small ones, a few centimetres in size,” says Huang. He takes a handful of maw that look like plastic, brown leaves from one side of the room, saying, “They come from the south of Brazil and cost a bit over 100 reais per kg ($17.70).”

These are some of the cheapest prices for fish maw, he says. “Restaurants in China buy these in large quantities to make stock.”

Yet, larger sizes do not mean higher prices. Huang picks up maws of 30 to 50 centimetres (11.8 -19.6 inches) in length. “Those big ones are from gurijuba (a kind of catfish) fish. They’re big but cheap, and don’t get a good price.”

Outside, a truck pulls up and unloads several sacks of yellow croaker maws. Huang takes two out, each one tens of centimetres in size. He knocks them together to judge if they are dry or not. “They should be transparent and not greasy,” he says. These are good ones.

The company has a quality controller who sorts the fish maw according to market demand. Size and shape are important, but the species is the real price determinant. The most expensive of all in this region is the yellow croaker’s maw.

“The market in China is huge. If there are goods, they’ll buy. What changes is only the prices for the maw,” says Huang.

Huang has been doing business in Brazil for seven years. “At first, I was buying a kg for about 1,000 reais ($176.80). It is 3,000 ($580.40) now but prices in China haven’t changed that much.”

With more companies competing for a share, profits aren’t what they used to be, he says, so he moves more volume.

Santos says Para has more than 10 companies like the one he and Huang run and many more traders working between the fishers and the exporters. One such trader, Ilto Silva, a former truck driver, said there are at least 50 in Braganca where he lives.

He buys “green” (undried) fish maw in nearby towns and takes them to a farm to be cleaned and dried before selling them to exporters. “Everyone sees the high prices and thinks it’s easy to make money,” he says. “But when you get started you realise how fierce the competition is [to secure a good price]. Also, more Chinese businesspeople are arriving.”

In a small fishing village near Braganca, next to a fishmonger, a small log cabin advertises that it buys fish maw. In Vigia, near where the fishing boats moor, one company has a painting of a yellow croaker on the wall, also advertising that it buys maw.

More than 10 years ago, there were maybe only a dozen or so people in the trade, Santos says. Now, he says, there are 400 or 500. The influx of new people means this once unobtrusive trade is harder to hide.

The sudden increase in fishing activity, driven by the fish maw trade, however, has people like Santos worried.

“No one knows how many yellow croakers are being caught,” he says, pondering his future. “All extractive industries in Brazil are meant to be regulated but we Brazilians always just go ahead and deal with problems later. We can never anticipate the problem.”

Threat of overfishing amid data shortage

Nobody, from local fisheries officials in small towns like Vigia and Braganca to the federal government, was able to provide much data on fish maw.

In response to a freedom of information request, the federal government said they have no data on how many fish maws are collected, nor how many fishers are collecting them. Brazil’s export data doesn’t list fish maw exports by species and can’t confirm details about the market.

Bianca Bentes, a professor at the Federal University of Para’s Aquatic Ecology and Amazon Fisheries Centre (NEAP), first came across the fish maw trade when she started researching fishing in the coastal regions in the mid-1990s. Bentes grew up in Santarem, which lies on the Amazon River, and the freshwater fish she was more familiar with do not have maws that can be exported.

“It’s a typical tragedy of the commons,” said Bentes. Thirty years ago, she could find 2.5-metre (eight-foot) yellow croakers at the market. Now, a 1.5-metre (five-foot) fish seems large. “That’s a classic symptom of overfishing. We know far too little about these fish.”

Bentes said that her university has attempted to study the life cycle of the gurijuba, the first fish known to have been caught for its maw, but they still don’t even know where it spawns.

Ze Raimundo, 50, a merchant and fisher who has been fishing yellow croaker for years, explained that even they don’t know how long it takes the fish to reach, for instance, 10kg, which would mean a large, expensive maw.

For valued maw from species like yellow croakers, bigger fish means more income, yet, the fishers aren’t managing stocks – they’re just fishing.

Elsewhere in the world, fish maw production has caused irreversible damage to ecologies. The most valuable fish maw used to come from the Chinese bahaba, also a member of the croaker family, known as the giant yellow croaker and found on the coast of China.

The trade in the bahaba was banned in China in 1989 when it was listed by the Chinese state as a Class II protected species, which forbids domestic trade of the species. Populations, however, continued to fall and in 2006 it was added to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species.

While the population of Chinese bahaba declined, the trade started to shift to the totoaba from the 1920s, again a fish in the croaker family, this time found in Mexico’s Gulf of California. But the vaquita, a species of porpoise endemic to those waters, has wound up in totoaba nets.

The vaquita is a bathtub-sized cetacean found only in the Gulf of Mexico and is listed by the IUCN as critically endangered. Fewer than 10 are thought to survive in the wild as a result of overfishing totoaba, which is considered a vulnerable species by the IUCN.

Totoaba fishing has attracted global media attention since 2013 when the urgency of the vaquita’s plight came to light. China, Mexico and the US have worked together on enforcement operations. Yet, illegal catching of the totoaba continues and the trade in its maw, which is more valuable per kg than cocaine, is controlled by a complex and highly organised criminal group.

Soaring exports

Dried fish maw is famed in China as one of the “eight treasures” and ranks alongside bird nests and shark fin in the country’s traditional culinary and medicinal culture. People in China are becoming more aware of the cruelty associated with shark fin and bird nests – finning of a shark often happens while the shark is still alive and bodies are discarded into the ocean, while bird nests are harvested from cave ceilings, sometimes before eggs are laid or killing baby birds in the process. The links between the fish maw trade and ecological concerns, however, are rarely drawn.

Yet efforts to better monitor the trade have emerged and biologists and fishing management researchers have been able to cross-check data in Hong Kong and in Brazil to an extent.

Hong Kong has a comprehensive system for tracking imports and exports but only started in 2015 to track dried fish maw as a unique item – it was previously classified as “dried fish”. Between 2015 and 2020, about 20,000 tonnes of fish maw were imported to the territory, with a declared value of 14 billion Hong Kong dollars ($1.7bn).

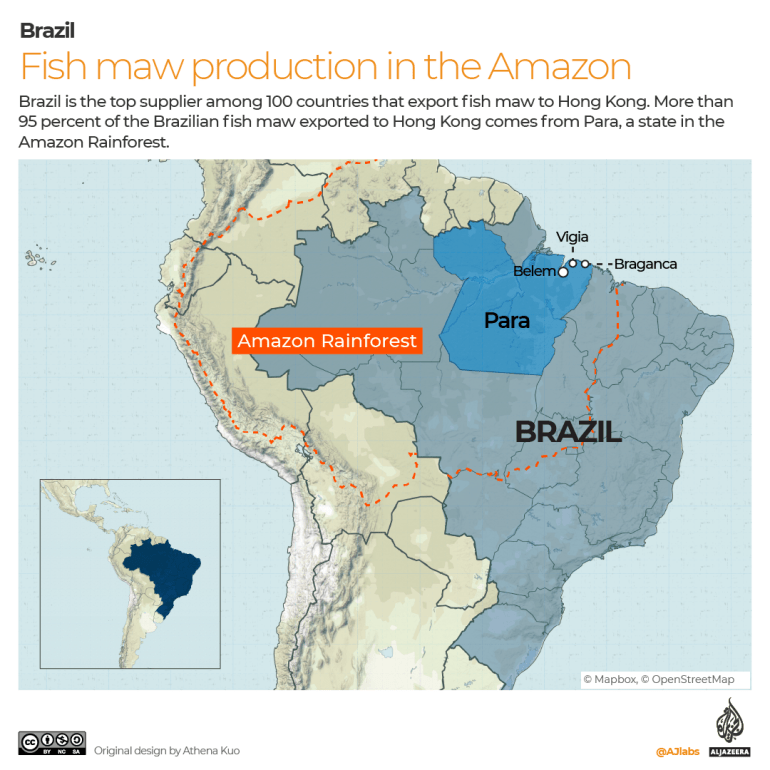

In Brazil’s official export data, there is no specific code for fish maw. But Hong Kong’s imports of fish maw from Brazil can be cross-checked with Brazil’s recorded exports of “fish by-products” for those years, 95 percent of which came from Para. The state of Amapa, north of Para, also produces fish maw but most is exported via Para.

According to Hong Kong’s Census and Statistics Department, the imports of fish maw between 2015 and 2018 came from more than 100 countries. Brazil was the biggest among them, with 3,300 tonnes worth 3 billion Hong Kong dollars ($384.9m).

Assuming fish maw accounts for the majority of fish by-products, in 2020, Brazil exported 637 tonnes of fish maw, a 398 percent increase on the 127 tonnes in 2012, the first year for which data is available.

Since 2012, both supply and demand were seen as stable.

Huang says things have been difficult for Chinese businesspeople with investments in groceries, restaurants and other food ventures in various Brazilian cities due to a worsening economy. This has pushed them to join the fish maw trade during the last decade.

Bentes thinks the boom in the trade in yellow croaker is linked to declines in catch since 2001 of the piramutaba, a type of catfish that is eaten but not used for maw. “Everyone in that trade shifted to fish maw.”

Research published by the journal Marine Policy in July 2021 confirmed that at least 10 species are now caught for their maw, compared with only one or two in the past. However, closed fishing seasons and size limits are only in place for the gurijuba. The yellow croaker is listed as vulnerable on the IUCN Red List. However, there has been no assessment of its numbers in Brazil.

Need for controls

Fish maw is given a dazzling variety of names in Chinese. These often reference the place of origin (“Indian sushui maw” or “Indonesian big mouth”), the shape (“egg maw” or “butterfly maw”), or the species of fish (“sea bass maw”). Often, the name reveals little: what’s called “north sea maw” may come from more than a dozen species of fish and various origins, most of which are from South America and not from any northern sea, as the name might suggest.

Fish maw is extolled for its various medicinal benefits. According to traditional Chinese medicine, it can stop coughs, prevent side-effects from other medicines, treat stomach or kidney problems, nourish the fetus, and enrich the blood. In Hong Kong and mainland China the prices between maw types differ from tens of yuan/Hong Kong dollars to tens of thousands.

The “golden croaker” maw (from the Chinese bahaba), though banned from fishing, remains the most highly prized: one maw once sold for more than $475,000 in 2012. New products keep appearing. A recent newcomer, the “spider maw”, named for its shape, is said to come second, selling for more than 55,000 Hong Kong dollars per kg ($7,054). Spider maws come mainly from Vietnam and Indonesia, from the Boesemania and other unspecified species, and its demand has already endangered one species of Boesemania.

The production of fish maw features on an inventory of Hong Kong’s non-tangible cultural heritage, where it is said to have medical value. Despite the treasured tradition, the collagen in fish maw is difficult to digest, according to modern medical science. Still, fish maw can be cheap enough to be an everyday food, and a more expensive product is regarded as an excellent gift. The priciest ones are collector’s items.

The market reminded Yvonne Sadovy, a professor at the University of Hong Kong’s School of Biological Sciences, of diamonds.

Like those precious stones, the value of fish maw largely comes down to “the impact of recognised ideal physical attributes”, Sadovy and her co-authors wrote in a 2019 paper.

For a diamond, these are carats, cut, colour and purity. For fish maw, they are size, thickness, species, origin and shape. Marketing by salespeople and consumer desires ultimately determine the value. Speculation by collectors – fish maw keeps well and is regarded as more valuable the older it gets – and even the links with organised crime are other similarities with the diamond market.

“The analogy breaks down when supply is considered,” Sadovy’s study said. “While diamonds in the ground are abundant, many fish species targeted are not, which means that controls on this segment of the maw trade are necessary.”

Sustainability an issue for all

At a free wifi spot built by the local government by the river in the centre of Vigia, people stop to enjoy the shade and the connectivity. When fish merchants, sellers of fishing gear and ice, boat captains and fishers, and drivers and guards sit together, fishing is what they discuss.

“There are more boats, so fish are getting cleverer,” says Silvio Sardinha, a boat captain, referring to how he caught little on his last 20-day trip. He mostly fishes for yellow croakers.

The previous exciting boom was shark fins, he says. But a decade or more ago the sharks were hunted to the point of extinction and a ban was put in place. “Then, it was fish maw.”

The shark fin trade flourished in Para until 2012, when Brazil ruled that sharks must arrive on land with their fins attached to their bodies, in order to ban finning. The fishing and sale of some species of shark were prohibited in the years that followed.

For those living in the Amazon, this is a familiar story. One “boom” after another has brought growth and then collapse. “It’s like gold mining: lots of miners, not much gold,” says Sardinha, swarthy and greying.

He tells us he started fishing when he was seven. He’s in his 50s now and operates a large boat with GPS and a cold store. It can spend 20 days at sea and has machinery to help pull in the nets.

Still, catching big fish requires big nets, and with fewer fish closer to shore, he needs to burn more fuel to travel further out to sea. Every time he comes back ashore, nets and fuel are more expensive, so he needs to earn more from the next trip.

Nobody knows how many fishing vessels work out of Vigia. Sardinha estimates there are 1,000. A nearby fishing gear trader reckons 500.

Diego Cardoso, Vigia’s secretary of Fisheries and Rural Development, who didn’t know either, only said fishing is the main economic activity in Vigia.

During the last 10 years, a once worthless waste product has become highly valuable – but many in the community wonder how long the prosperity and supply can last. Those who depend on fishing know better than anyone else that the only limit to how many fish can be caught is how many fish there are in the sea. On the riverbank, fishers count the number of species they’ve seen disappear on their fingers.

“I worry for my grandkids. What will things be like then?” asks Sardinha.

High prices and unregulated supply bring temporary prosperity – but a collapse of that supply often follows. Worse, fishers take on debt to increase their catch and lose negotiating power.

Sadovy, the professor in Hong Kong, said in an interview that she has seen this pattern in ocean fishing many times, with other types of products, in other parts of the world.

But it doesn’t have to be like that, Sadovy added. If fishers could organise to manage their resources, they could take back control of prices; if consumers realised that when a species faces extinction they lose the product altogether, they might consume more consciously.

“If we can better manage the ocean, we could gain more from it,” she sighed.

Paulo Amaral, a senior researcher at the Institute of Man and Environment of the Amazon (IMAZON) from Belem, argued fishing is a potentially more sustainable source of income for Amazon communities, affecting the forest less than livestock and grain crop production. But it must be regulated. “There is still a great lack of inspection and control over what is fished,” Amaral said.

Something else to catch

Near Vigia, Junior holds generations of fishing knowledge in his head. There are more boats now – and more pirates, sometimes violent, lured by the expensive fishing gear and valuable catches like fish maw.

It’s risky to go out to sea alone or put new fishing gear on board. Nor have the tides been right lately. “But wait for the moon to come out,” he says, referring to a good time for fishing, as he fixes a net. “We will hear the yellow croaker croaking.”

This sound is where the croakers get their name. Croakers gather when searching for mates. The male fish uses its maw to make a knocking sound — the muscle that makes it contract is the fastest known among vertebrates.

“Sometimes you can hear it from the deck,” Junior adds, “Sometimes we go below deck to listen through the hull, or just get into the water. It’s like a hammer – bang, bang, bang.”

If Junior could meet some old Hong Kong fishers, they’d have plenty to talk about. Back in the 1960s, the Chinese bahaba used to make the same noise in the waters to the west of Hong Kong. The fishers would press their ears to the hull of their boat to track the fish. Fish weighing as much as 40kg were caught then, sometimes even weighing up to 80kg.

Another fisher arrives to fix nets and Junior laughs. “Don’t go telling us China’s going to stop buying fish maw,” he says, gesturing at the new arrival. “There was a rumour about that once and this guy almost had a heart attack.”

After the midday siesta, the village of Itapua starts to stir, having escaped the harshest of the daytime humidity and heat. Someone joins Junior to sort out the net and points at the mangrove swamp. If the fish maw trade ends, they say they can catch crabs.

Those who grew up here know that if you stick an arm into the muddy swamp and wait a few minutes – it will come out covered in crabs. Another fisher laughs at the idea: “You get one real for a crab ($0.18). One hundred crabs, 100 reais. Can you get a 100 in a day? Even if you do, it’s still not enough to feed a family!”

Everyone shakes their head, saying things will be OK. There will be something else to catch in the sea.

This story was produced with support from the Rainforest Journalism Fund in partnership with the Pulitzer Center. A Chinese version of this story is published at Initium Media and can be read here.

Source: Al Jazeera